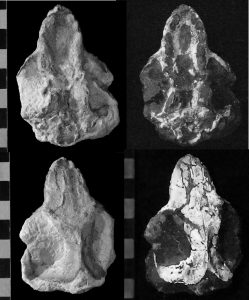

Cifelliodon wahkarmoosuch; A small newly discovered fossil with great significance discovered in southeastern Utah.

Utah Highlights

- A fossil mammal discovered by Utah Geological Survey paleontologists in eastern Utah reshapes the scientific understanding of the Earth’s ancient supercontinent, Pangea. Because of this finding coupled with newly discovered dinosaurs from the same rocks, scientists now understand that Pangea separated about 15 million years later than previously thought.

- Among the many dozens of Cretaceous (145 million to 65 million years ago) mammal species known in Utah from isolated teeth and jaw fragments, this 130 million-year-old fossil is the first mammal skull to be found in Utah’s Cretaceous rocks.

- Named Cifelliodon wahkarmoosuch; it comes from an extinct group of primitive mammal relatives known as the Haramiyida, not previously known from either the Cretaceous or North America.

- ‘Cifelliodon wahkarmoosuch’ means Cifelli’s tooth of the Yellow Cat strata. In Ute tribal language wahkar and moosuch mean yellow and cat, respectively. Yellow Cat is the name of the rock unit in which the fossil was found. The genus name honors Oklahoma paleontologist Richard Cifelli for his contributions to Cretaceous mammal research in Utah and the American West.

- Cifellidon would have been so primitive that while covered in fur and suckling its young, it would have lain eggs like the modern platypus.

- Andrew R.C. Milner, a paleontologist at the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm, discovered the skull site on Bureau of Land Management Lands northeast of Arches National Park.

- Paleontologist unexpectedly found the skull in the lab under the foot of a new iguanodont dinosaur called Hippodraco.

- Cifelliodon wahkarmoosuch weighed about 2.5 pounds, probably had short legs, and likely only stood about 6 inches tall. Broad molars suggest its diet consisted of leafy and fleshy vegetation. It also had buck teeth, a shallow snout and a downturned face. Scientists reconstructed the form of its primitive brain using CT scans. Large olfactory bulbs indicate that it had an excellent sense of smell, which suggests that it may have been nocturnal.

Full Press Release

Utah fossil reveals global exodus of mammals’ near relatives to major continents

A small fossil is evidence that Earth’s ancient supercontinent, Pangea, separated some 15 million years later than previously believed.

A nearly 130-million-year-old fossilized skull found in Utah is an Earth-shattering discovery in one respect.

The small fossil is evidence that the super-continental split likely occurred more recently than scientists previously thought and that a group of reptile-like mammals that bridge the reptile and mammal transition experienced an unsuspected burst of evolution across several continents.

“Based on the unlikely discovery of this near-complete fossil cranium, we now recognize a new, cosmopolitan group of early mammal relatives,” said Adam Huttenlocker, lead author of the study and assistant professor of clinical integrative anatomical sciences at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

The study, published in the journal Nature on May 16, updates the understanding of how mammals evolved and dispersed across major continents during the age of dinosaurs. It suggests that the divide of the ancient landmass Pangea continued for about 15 million years later than previously thought and that mammal migration and that of their close relatives continued during the Early Cretaceous (145 to 101 million years ago).

“For a long time, we thought early mammals from the Cretaceous (145 to 66 million years ago) were anatomically similar and not ecologically diverse,” Huttenlocker said. “This finding by our team and others reinforce that, even before the rise of modern mammals, ancient relatives of mammals were exploring specialty niches: insectivores, herbivores, carnivores, swimmers, gliders. Basically, they were occupying a variety of niches that we see them occupy today.”

The study reveals that the early mammal precursors migrated from Asia to Europe, into North America and further onto major Southern continents, said Zhe-Xi Luo, senior author of the study and a paleontologist at the University of Chicago.

Fossil find: a new species

Huttenlocker and his collaborators at the Utah Geological Survey and The University of Chicago named the new species Cifelliodon wahkarmoosuch.

Found in the Cretaceous beds in eastern Utah, the fossil is named in honor of famed paleontologist Richard Cifelli. The species name, “wahkarmoosuch” means “yellow cat” in the Ute tribe’s language in respect of the area where it was found.

Scientists used high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scanners to analyze the skull.

“The skull of Cifelliodon is an extremely rare find in a vast fossil-bearing region of the Western Interior, where the more than 150 species of mammals and reptile-like mammal precursors are represented mostly by isolated teeth and jaws,” said James Kirkland, study co-author in charge of the excavation and a Utah State paleontologist.

With an estimated body weight of up to 2.5 pounds, Cifelliodon would seem small compared to many living mammals, but it was a giant among its Cretaceous contemporaries. A full-grown Cifelliodon was probably about the size of a small hare or pika (small mammal with rounded ears, short limbs and a very small tail).

It had teeth similar to fruit-eating bats and could nip, shear and crush. It might have incorporated plants into its diet.

The newly named species had a relatively small brain and giant “olfactory bulbs” to process sense of smell. The skull had tiny eye sockets, so the animal probably did not have good eyesight or color vision. It possibly was nocturnal and depended on sense of smell to root out food, Huttenlocker said.

Supercontinent existed longer than previously thought

Huttenlocker and his colleagues placed Cifelliodon within a group called Haramiyida, an extinct branch of mammal ancestors related to true mammals. The fossil was the first of its particular subgroup – Hahnodontidae – found in North America.

The fossil discovery emphasizes that haramiyidans and some other vertebrate groups existed globally during the Jurassic-Cretaceous transition, meaning the corridors for migration via Pangean landmasses remained intact into the Early Cretaceous.

Most of the Jurassic and Cretaceous fossils of haramiyidans are from the Triassic and Jurassic of Europe, Greenland and Asia. Hahnodontidae was previously known only from the Cretaceous of Northern Africa. It is to this group that Huttenlocker argues Cifelliodon belongs, providing evidence of migration routes between the continents that are now separated in northern and southern hemispheres.

“But it’s not just this group of haramiyidans,” Huttenlocker said. “The connection we discovered mirrors others recognized as recently as this year based on similar Cretaceous dinosaur fossils found in Africa and Europe.”

skull composite taken in 2007

Quarry location outside of Moab, Utah.

# # #

David Grossnickle and Julia Schultz from the University of Chicago also contributed to the study.

The specimen was found on the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management lands (permit UT-EX-05-031) and is held in the public trust at the Natural History Museum of Utah, where it is on display in the museum’s Past Worlds Gallery.

The federal government provided $300 for the research. The remainder was supported by the state of Utah.